What is natural beauty anyway?

This article is part of our special series on Flesh

Dom Bridges is the founder of Haeckel’s, a luxury natural skincare company based in the English coastal town of Margate. Haeckel’s began with a bar of seaweed soap that Bridges made from red and green algae from the beach and their products today leverage the healing, calming properties of kelp, dulse and wrack. Last year, Haeckel’s received an investment from Estée Lauder which will allow the company to scale up to meet market demand and reposition the brand for further growth. Here, Bridges speaks to ReD’s Maya Potter about nature as technology, changing perceptions around natural resources and why salt water heals all wounds.

The world of natural beauty often celebrates the virtues of organic products sourced from nature and rejects the idea of soulless products made in sterile laboratories or factories. Nature is deemed gentle and pure, and the man-made harsh and polluting. The clean beauty movement questions industrial chemicals effects on the body and the environment. Through this lens, science seems artificial, sterile, even, toxic.

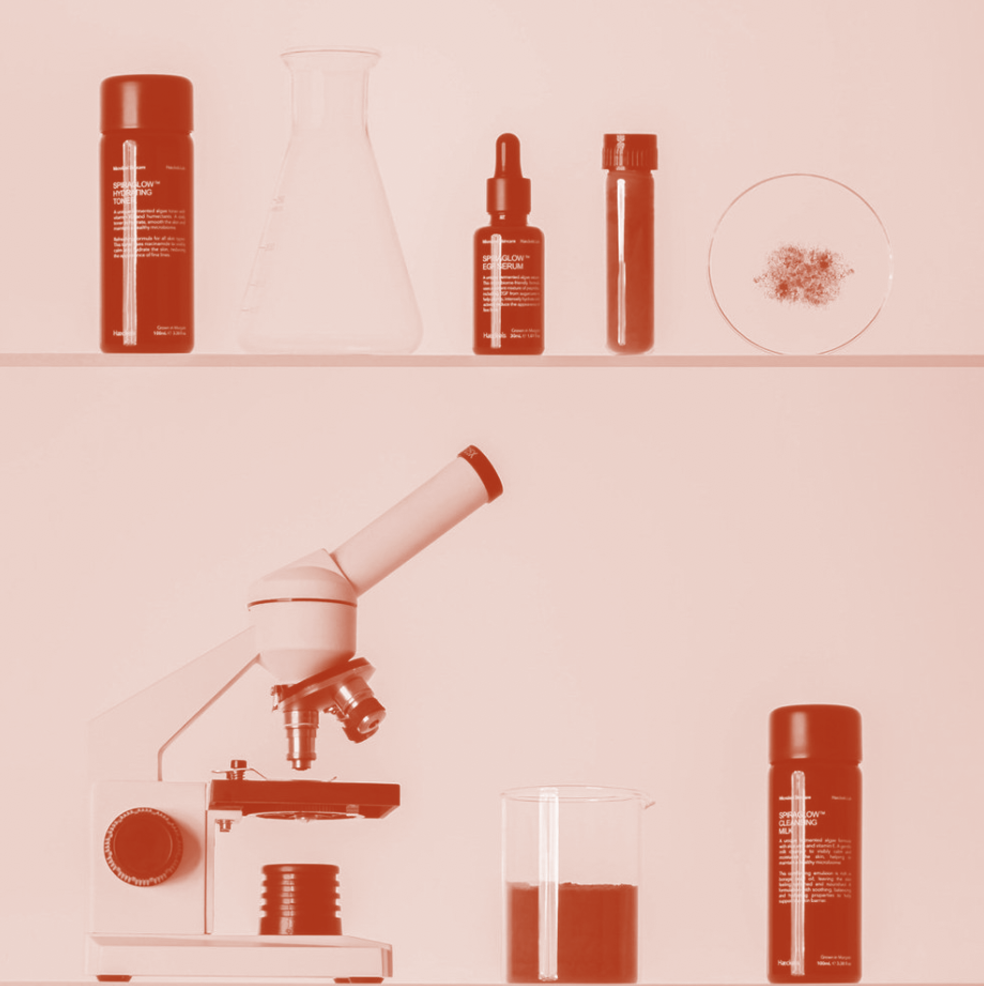

Haeckels seems to have resolved this conflict. Implicit in the brand ethos is a desire to reintroduce life and wildness to a sterile, artificial cosmetic industry while simultaneously exploring the science of life and wildness itself. The brand’s dreamy visuals draw on Bridges’ background in film and advertising. Bridges reintroduces us to the sensory romance of the coast, to mist and waves, greys and whites. The Pluviophile candle smells like the ground after rainfall and their nameless perfumes have GPS coordinates that tie the fragrance to places along the English coast.

Amid today’s hyper body-consciousness, Haeckels is not selling the sex of skincare – but rather its romance, encouraging us to let go of the expectation to embody beauty – and in an unself-conscious way, simply experience it. To this romance, Bridges stresses that nature itself is high-tech. Haeckels is diving deep into the biology, the life of the skin and flesh, soil and sea.

Through this experimentation, Haeckel has raised the bar for what sustainable innovation means in the skincare industry, for example by using mycelium packaging and seals made from algae. Haeckel’s wraps their boxes in wild seed paper – when introduced to water and soil, activates the seeds, sprouting new life. He challenges the industry to step up: don’t make more products, make better ones.

Bridges invites us to marvel at the beauty and complexity of our own biology – diving deep into the body’s microbiomes; our skin expresses the state of our gut. To Haeckels, “Beauty is on the inside”, quite literally.

Maya Potter: I was struck by something you said in a recent interview: “Customers are bored with the word ‘natural’ and labels such as ‘clean beauty’ need more clarification.” Can you elaborate?

Dom Bridges: There’s a new enforcement coming demanding clarification on exactly those terms, which can cover all sorts of sins – and even, cover up some good deeds too. Let’s not beat around the bush, as a concept, I consider “natural” kind of dead but it’s still used and some brands will still try to stick “natural” on their soap at Christmas time. In terms of how we’ve used it, I see it as a bridge. There are so many miscommunications – like micro-beads, acids, all these terminologies. As a company we stay away from anything like that – whenever there’s any data surrounding it that it has a negative result on skin or health. How the hell do you communicate that? Well, “natural” is a good way. Using the word is only a bridge to get to somewhere else – for us to understand what we’re doing, for us to become better communicators about what we’re trying to achieve.

Maya: In addition to the critique of the natural, the industry now has a more lab-based, medicalised approach to skincare. What are your thoughts on that?

Dom: I think it’s really valid. We’ve gone into lab-grown ingredients as well where we’re 100% responsible for what is coming into existence. It would be hard to classify something that we’ve grown in a lab as “natural” – there is no till, no pesticides. It is a different relationship than buying an active off a shelf or even pulling an ingredient out of the ground, and extracting it. When you’ve 100% created it, you could argue that is better than natural.

“Natural, artificial – one can’t exist without the other, right?”

Maya: What is your take on the natural-artificial boundary?

Dom: Natural, artificial – one can’t exist without the other, right? It’s not like there’s a battle between the two. It’s just about origin – where it comes from, what the definition is, who’s responsible for what, you know? And how you effectively enlighten people about how it came to be. It’s really just a disconnect, isn’t it? We’re so far removed from interfacing with life outside that the perception is that it is dirty or that it is low-tech. I’ve been exploring the ways that technology exists in nature. There are complexities within ecosystems which we should really refer to as technology – rather than thinking that tech is only something that is clean or digital. It would be nice to start to change that language. That might help to start to break down this perception that what we perceive to be dirty or a weed is somehow not as important, relevant or basic.

Maya: I was fascinated by your instinct to take seaweed, which you’ve said people saw as dirty, and transform it into a bar of soap, the epitome of cleanliness. What prompted that transformation?

Dom: When it started, it was about abundance. We had chest-high mounds of seaweed here in Margate. People’s association with it was like, “What’s this dirty kind of thing tied around my ankles?” It’s quite rare that you have an abundance of a natural resource and it be something that everyone’s moaning about: “It stinks. It’s in the way. Why can’t we get rid of it? It’s in the water.” I spent some time in Japan and China where people were shoving seaweed down their throats. I thought: this is just classic English nonsense. There’s an opportunity here staring us in the face. The switch around is presentation.

Maya: What are the main considerations when Haeckels is developing a product?

Dom: I think about the reason for it to exist. You have to be able to really rationalise why on earth you are making this thing in the first place. Not because five other companies make that product with the same extract or whatever. That’s not enough of a reason. Just because your bottle looks better, that’s not enough. It’s got to have a reason to exist. More often, it should be about not making something as well and reformulating a product and making it better. It’s got to be relevant. What I mean by being relevant is defining what it is that the product actually does for us as humans.

Maya: Can you tell me about your tag line, “Salt water heals all wounds”? How do think about harm and healing?

Dom: Obviously it doesn’t but, I just love the different levels of it, you know? It’s just a loaded kind of comment. Salt water definitely has a healing capacity. If you do cut yourself, then jumping in the sea will definitely help your epidermis recover quicker and clean it. The other side of it is this idea of crying or swimming as cleansing. The coast has an uninterrupted view of a horizon line that allows your brain to be free. Spiritually, creatively, emotionally, the ocean has the capacity to cure those wounds as well. It definitely has done that for me, which is why I still use that statement. It still means so much to me. You can pick it apart in one context and then in another context, it makes perfect sense.

This interview is part of our special series on Flesh